How Liberalism Lost the Majority

Liberalism’s own principles have sown the seeds of its decline. To speak to the majority again, it must evolve

This essay opens a four-part series on rearticulating liberalism for today’s world. Liberalism once thrived as a creed of emancipation, breaking shackles imposed by communities and states. But as contexts have shifted, its own principles have sown seeds of its decline. To regain its power to inspire majorities, liberalism must evolve. In the coming essays, I will explore three areas where I believe renewal is most urgent - the nation, governance, and culture - to sketch a possible framework for liberalism’s future. These ideas are offered not as final answers but as a frame to spur debate and sharpen our collective thinking about liberalism’s future.

Just decades after Francis Fukuyama declared the "end of history" - suggesting liberal democracy had achieved ideological victory - liberalism is now on the backfoot worldwide. It has lost legitimacy, and liberal parties have lost state power. In response, liberal political actors have become consumed by tactical maneuvering to regain office without rethinking the liberal platform to regain relevance and mobilise the masses. In the urgency to win immediate fights, liberals are in danger of losing the larger war of ideas.

The tactical focus is, of course, vital. One of liberals' core critiques has been their disconnect from people's lived realities, so grounding in local concerns offers valuable lessons. All ideologies rely on state power for propagation, but liberalism is especially tied to state institutions - leaving liberals particularly bereft when confronting aggressive populist governments. Winning elections, with all their minutiae, remains essential.

The problem with tactics alone

However, an overriding focus on tactics hurts liberalism both short and long term. People want their lives to have meaning and to feel part of something bigger than themselves. For a time, liberalism was able to provide that, underpinned by uneven but genuine progress. It offered a vision of free citizens living together under equal law, with governments accountable to the governed and power transferred peacefully through elections. It balanced individual freedom with diversity, protected minorities, and restrained arbitrary rule.

This remains a vision worth defending. But today, liberals struggle to articulate it in a way that resonates. To recover the capacity to inspire, liberalism needs a coherent ideological rearticulation - not just a mishmash of local tactics or tired calls to "resist" and "save democracy." It needs a story that ties ground-level maneuvers to a shared vision. This story must marry universal liberal principles with locally resonant moral purpose - connecting the personal to the political, and giving citizens not only rights but a shared vision of the society they should help build.

In a reversal of sorts, the Right offers a global framework where each country can plug into the larger rubric of place-based nationalism, tradition, majority culture, and respect for authority and order. These provide identity and community across countries. Liberalism, by contrast, offers universal principles - but this very universalism, coupled with the economic and social dislocations of globalisation, financialisation and technological developments, has undercut its local resonance and discredited the appeal to institutions and procedures.

Why liberalism lost ground

Liberalism itself emerged as a response to particular contexts. It took shape first in reaction to religious wars and later as a way to restrain the absolute power of the state. Over time, political liberalism twinned with economic liberalism and positioned itself as an ideology designed to break shackles: to restrain oppressive communities, to check overbearing states and ensure accountability, and to create space for individual freedom and self-expression.

When social cohesion was relatively strong, the public sphere unified, and institutions trusted, liberalism functioned as an emancipatory ideology. Principles like free speech and individual rights expanded freedom without destabilising society, because other actors - social, religious, community, professional - acted as moderating (gatekeeping) influences. Liberalism could afford to be radical about emancipation because society provided its own forms of restraint, even if at times unreasonable.

But the context has changed dramatically. Globalization, financial capitalism, and technological disruption have eroded communities and fragmented the public sphere. Institutions have lost credibility. Gatekeepers - from editors to party organizations - no longer command respect or control. Markets fuel innovation but also massive inequality. The same liberal principles that once were emancipatory now contain the seeds of fragmentation, mistrust, and concentration of economic power.

Free speech still enables dissent and accountability, but it also enables misinformation, polarization, and hate. Individualism still empowers autonomy, but it also accelerates atomization and drift. Capitalism has shifted from decentralised competition to active concentration of power.

The liberal elite did not adapt to these changes. They kept reiterating original articulations, often dismissing and disparaging those who argued otherwise. Too often, it seemed that they defended institutions less to preserve fairness than to preserve their own standing.

Beyond proceduralism

This is why institutional and procedural defenses of liberalism ring hollow. To the public, it is not always clear if what is being defended is fairness and expertise or elite privilege. This is especially so because liberals are hesitant to take clear positions on issues the average person understands - identity, community, aspiration, public order - for fear of marginalising sections of society. They are most direct in opposing rightwing leaders and regressive traditions, conceding grievances only when cornered - such as the impact of globalisation and technological advancements on affected communities. On most issues, liberals retreat to process, as if neutrality can substitute for values. The result is that liberals appear effete and self-dealing, unable to say what kind of society they seek to build.

Individual freedom, rule of law, peaceful transfer of power etc all remain essential. But they are not sufficient to mobilize mass support. People rally around outcomes and moral clarity, not rules.

The need for rearticulation

Liberalism’s decline is in part due to its own failure to evolve and moderate itself. Principles that serve liberation also require self-restraint. Rights that secure pluralism also need to be balanced with responsibilities of coexistence. Individualism and self-expression can be emancipatory but can also lead to loss of meaning and drift. Economic liberalism that fueled innovation is now leading to extreme inequality and concentration of power.

Outrage and opposition to populists are ineffective. It is no use arguing they are undemocratic when they came to power mobilising grievances that the liberal establishment presided over.

What liberalism needs today is rearticulation. That rearticulation must preserve liberal principles while embedding them in frames that resonate locally and give meaning to people’s lives.

A new beginning

Liberals have followed a tactical array of outrage against populists, defense of institutions and a basket of welfare policies. However, these are inadequate. Institutions cannot survive without imagination, and procedures cannot endure without purpose. Liberalism will recover its strength only when it regains the ability to inspire majorities and meet the deeper yearnings for meaning, belonging, and order that populists have tapped into. This means accepting that liberalism cannot just keep repeating its original articulation in the present tense. If it wants to be more than a rear-guard defense, liberalism must rearticulate itself for today’s realities.

Liberalism thus needs to refresh its platform on issues like the kind of society it seeks to build, governance, identity and opportunity in ways that resonate locally. In subsequent essays I will argue that liberalism must reconnect to nation, governance, and culture if it is to capture public imagination again.

Next essay on Liberalism and the Nation

A small note: I’ve been considering moving more of my writing to this blog. While newspaper op-eds offer wide reach, they also come with constraints - the need for a news peg, word limits, and delays between writing and publication. Writing here allows greater flexibility in form, timing, and tone.

If you’ve found any of these pieces valuable, I’d appreciate your sharing them with others who might find them worthwhile as well.

Also Read:

Reclaiming the Nation for Liberalism

This essay is the second in a four-part series on rearticulating liberalism for today’s world. Liberalism once thrived as a creed of emancipation, breaking shackles imposed by communities and states. The first essay argued that liberalism failed to evolve as contexts shifted, and its own principles helped sow the seeds of its decline

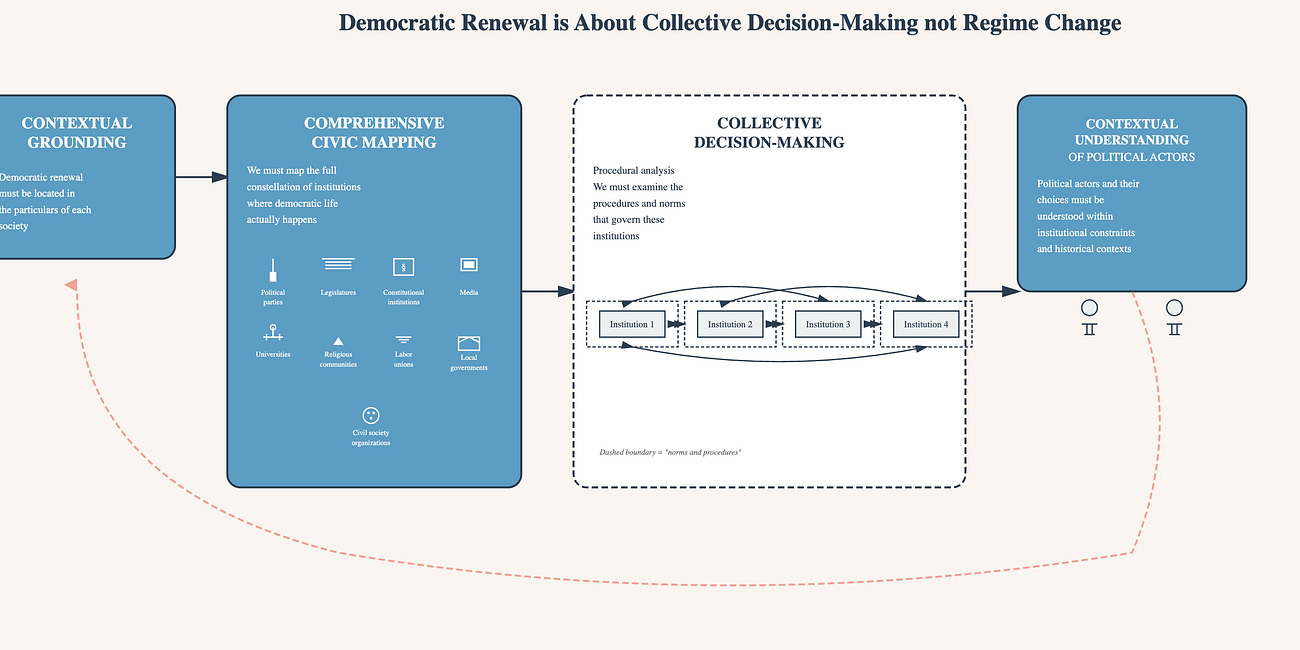

Democracy is More Than Regime Change

In recent years, I’ve found myself in frequent conversations marked by a shared sense of ennui and listlessness. Fear and intimidation gradually erode collaboration and solidarity, leaving people isolated. Idealism without a practical outlet commensurate with its ambition can begin to feel foolish. And when collaboration or solidarity is scarce, the pra…

San Francisco and the Limits of Full-Tilt Liberalism and Capitalism

I went to San Francisco for the first time last month. The city was dotted with homeless people, visible mental illness and open drug use. Signs were everywhere warning not to leave valuables in cars. Downtown felt lifeless, half the stores had shut shop. As I walked around, I thought to myself that this was the logical culmination of full tilt liberali…

Indian Liberalism lost in 1950s when the real liberals(Classical Liberalism) lost to Fabian Socialism.

Modern Liberals are “Political Progressives” which is a deviation from the original liberal traditions since the days of John Stuart Mill. It's the same in USA.

Economically a centre-right has more in common with the classical Liberals than Modern Liberals.

I think it’s hard to say your analysis is wrong, but it’s incomplete. Liberalism in the broad sense you’re talking about didn’t get here accidentally, pretty much every flaw you mention was a consciously sought objective. Part of modern liberalism’s self-definition includes abolishing non-universal groupings of people like nations, religious communities, etc. Part of liberalism’s understanding of authoritarianism requires it to be fundamentally against hierarchical structures and anything that looks like concentration of power, resulting in the obsession with process and the lack of accountability which comes with no one being ultimately responsible.

I think the reason for that is liberalism wasn’t ever something designed to be a comprehensive ideology of governance. In any period or place where it could said to have worked well you’ll see it being attached to something else. Recently that was the idea of the nation-state, but as concepts of patriotism and national pride became viewed with suspicion that vital half sort of rotted away. Before that liberalism even managed to thrive under monarchies like in the English Whig supremacy or Napoleon, but it still needed that support.

Liberalism alone is just a frame, individual liberty and fairness are not ends unto themselves, and any revival must recognise that liberalism’s success in the first place came due its being attached to other structures which it then went on to kill.

As a side note, democracy doesn’t actually have to be liberal definitionally. It can be argued since the new deal on liberalism had a good run and pushed back against many of the excesses of the order before it, and now the same is happening with a new order which is pushing back against the excesses of liberalism. Sure it’s sort of flailing and unsophisticated but even FDR started by prolonging the Great Depression, those things just improve in a pseudo Darwinian way and you can already see it happening. You keep using the word populist as a slur but at least it’s bringing back a sense of identification for people with their states which is rooted in democracy for legitimacy. Even materially it’s hard to say India is worse off today than 2014, or that things would be better with left populists rather right populists in charge, which seems to be the only alternative INC and co seem to have found to combat the BJP.

Apologies for the long comment.