Reflections on the Bihar Election and Party Campaigns

Parties often become absorbed in their own priorities, which are not always the issues that move voters

Many years ago, when I headed a national student organisation, we often debated which issues would help us broaden our appeal among students. One theme that returned in every meeting was the demand to restart student union elections in states where they had been suspended. Elections had been halted because of campus violence and other concerns, but the long pause has had wider consequences. Universities have slowly been drained of political energy, and the pipeline for new student leadership has weakened. At the same time, student unions’ affiliation with political parties has had repercussions not entirely positive. Instead of channeling student concerns upward, party-affiliated student unions often function as mouthpieces of party leadership. This can polarise and vitiate the campus atmosphere and alienate sections of the student population. In a healthy democracy there is a dialectic in which parties identify and mentor young talent while student leaders keep parties connected to the everyday problems of students. Consequently the way forward is not a simple start or stop student union elections. However, this is not a discussion on student politics, which is a larger and more complex topic and needs its own separate discussion.

The purpose of referencing this argument here is different. The idea of restoring student elections repeatedly came up as a top issue for expanding reach, yet this was a misreading of the student landscape. For most ordinary students this is not the central concern. Low voting turnout in places where student union elections do happen is one indicator. More fundamentally, the divide is not between students who support or oppose elections but between students who are already politicised and those who are not. For the former, elections are existential and symbolically important. For the latter, they may not register as a paramount concern. What seemed like a universal student demand in those closed-room discussions was in fact the priority of those already inside the political arena, not those outside it.

A similar pattern is visible in the parent parties. Leadership circles often become absorbed in their own priorities, which are not always the issues that move voters. A useful example from 2019 was the attempt to appeal to the female electorate built around the slogan of bringing more women into legislatures. The case for greater female representation through reservation is unimpeachable. What is less clear is whether this is top of mind for the broader female electorate or mainly with women who already see a political path for themselves. In 2024, the improved performance of the Opposition was attributed by some to the resonance of the “save the constitution” campaign. This is a wrong interpretation. The campaign resonated in some states because of the ability of the leadership to directly link it with reservation, an everyday issue for the dalit community, not because of the broader constitutional messaging. There is often quite a bit of distance between moral correctness and electoral salience. The lesson is not that democratic arguments never land but that they gain traction only when voters experience them as connected to their immediate social and economic position.

The same gap appears in campaigns built around abstract ideas of saving democracy or protecting institutions. These themes are vital for the long term health of any republic, but they rarely gain traction with voters who are contending with immediate pressures in their daily lives. The pattern is not unique to India. In the United States, the Democratic Party has steadily lost ground despite repeated warnings about democratic backsliding. Its stronger performances have come only when abstract democratic concerns were translated into specific, localised threats rather than left as general alarm and more recently, when it shifted attention to practical concerns, most visibly the cost of living.

It is important, however, not to romanticise the idea of raising people’s issues. Identifying an issue is only the first step. Elections demand a sequence of tasks that include careful articulation, sustained communication and, finally, the ability to convert support into votes. Organisation is the thread that connects these stages. Without an organisation that is spread across the length and breadth of the electorate and trusted on the ground, even the most astute identification of voter concerns remains inert. Organisation cannot substitute for a compelling political narrative, but without it even strong narratives tend to dissipate (this explains in part the disappointing debut of Prashant Kishor in this Bihar election).

There is also a conceptual conceit in speaking of people’s issues as if the electorate were a single, coherent entity. Every society contains divisions, and these divisions produce different, often conflicting aspirations. The same individual may hold views that cut across categories, esp social and economic. The vote remains a blunt instrument in a binary contest and cannot capture the full range of preferences. The task for any political formation is therefore not only to locate the right issues but to build the organisational strength that can interpret and aggregate these varied demands into a credible political offer to cobble together a viable majority.

Two closing thoughts. First, an election season can rarely sustain more than one coherent campaign. Organisations need time to prepare, and messages need time to move through their internal channels before they reach voters. A campaign built on multiple themes unsettles the organisation and confuses the electorate. Nor can an election campaign carry the burden of political education. That work belongs on a separate track through party wings, affiliated bodies and civil society groups. Their role is to shape opinion, build literacy and create the conditions in which a political message can later take hold. The purpose of an election campaign is different. It is about assembling a majority and winning power, and this requires grounding the campaign in issues that voters grasp immediately.

Second, every leader of a large organisation, certainly in politics, receives a constant stream of feedback. Much of it is contradictory. The ability to judge what to absorb and what to set aside is central to leadership. All leaders make mistakes, but the capacity to course correct quickly is key. The ability to gauge when to course correct and when to persist with a strategy is as important. Persistence matters, since many strategies require time before they gain traction. Yet persistence can also trap an organisation in a losing approach, with defeats rationalised in various ways. Leaders also operate within organisations where internal incentives reward intra-party signalling more than external listening, which compounds misreads of voter sentiment. Recognising this structural feature is important for understanding why course correction often arrives late. Here leaders must weigh two sources of feedback: their organisation and the electorate. Election defeats are one form of feedback, and they are usually the clearest.

Finally, the argument about institutional independence and a level playing field is hugely important and cannot be overstated. However, even these structural constraints cannot become a blanket explanation for every defeat, otherwise strategy becomes impossible. In fact, if the assessment of these institutional biases is perceived as being decisive, then a different set of political strategies is required, as opposed to the post hoc explanation of defeat after contest. See “coda” below

India is at an inflexion point. We have the world’s largest youth population at a time when the usual paths of upward mobility are under strain due to the disintegration of the global order as well as advances in technology. The role of our political parties in charting a way forward for India, one that broadens its opportunity landscape and enhances its contribution to the world, cannot be overstated.

The opportunity to learn about one’s country and to represent a country and its people is a privilege like no other. It demands openness to a wide range of experiences and the willingness to engage with disagreement. Too often dissent is dismissed by labelling those who disagree as cowardly, corrupt, complicit or anti-national! At the very least, dissent signals independent thought and should be evaluated on its substance to do justice to the country and organisation. If political organisations are to meet the moment, they must create internal cultures where such dissent is not merely tolerated but treated as essential feedback rather than disloyalty.

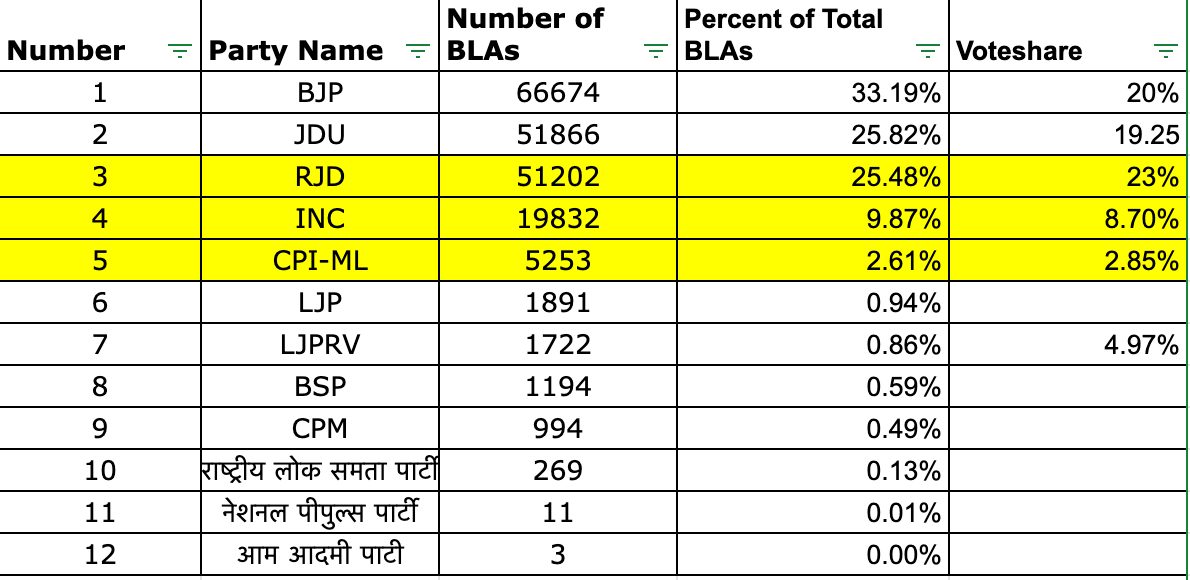

Coda: There is no question that the Bihar election was not fought on a level playing field. The EC allowed the disbursement of Rs 10,000 to women in Bihar *during* elections while disallowing similar government interventions in Opposition ruled states. The SIR too was initiated - and implemented - in a ham-handed manner and was instrumental in not cleaning the rolls as much as it was in destroying faith in the process. It was only the widespread furore and Supreme Court’s intervention that somewhat salvaged the SIR process. Having said that, the question is - was this institutional bias DECISIVE in the election outcome? It doesn’t appear so based on multiple conversations with people not at all in the Government’s corner. The SC made the ECI upload the list of 65 lakh voter deletions and if there was a large number of illegitimate deletions, it is expected that some of it would have spilled over in the public domain through reportage and protests. Second, to conclude that the Rs 10K swayed women voters so completely feels uncharitable and also unrealistic. In states where all parties give money to voters, are voters trapped in some kind of Sophie’s choice or do they manage to cast their vote anyway? At the same time, a closer review of voter rolls through the ongoing organisational process (BLAs etc) is warranted during preparation and before elections.

Also Read:

Why SP Escaped “Goonda Raj” but RJD Cannot Shake “Jungle Raj”

By all accounts, it appears that the RJD suffered from a negative perception of “jungle raj” even though it has been twenty years since Lalu last governed Bihar. Whether that has a decisive impact on the result will become clear tomorrow when the votes are counted. But it is striking that the SP, with a similar Muslim–Yadav base and which was thrown out…

SC-ST seats are not an indicator of SC-ST popularity

In the aftermath of elections, a lot of questionable analysis - seemingly based on hard “data” - is doing the rounds. Some of it is rhetorical put out for partisan not analytical purposes but even the news media is putting out such obviously flawed reports that it hardly seems possible that the analysis was subjected to any editorial vetting at all. So …

Your point about the gap betwen elite priorities and voter concerns is spot on. Its remrkable how often party leadership remains in echo chambers rather than engaging with ground realities. The student union example perfectly illusrates this disconnect. What matters to those already politicized rarely mirrors the priorities of ordinary citizens dealing with bread and butter issues.

Independence of institutions is a bit understated.

In Bihar context, SiR for almost 8 Cr voters in 30 days, substantial deletions & bogus addition and tactic approval of Supreme Court of a flawed process and stonewalling opposition objections played a major role in opposition's defeat.

Practically, opposition participated in election where result was almost pre-decided.

Neither national nor local including employment issues raised by opposition could make any impact on the face of bribery to voters & tactful tinkering of voter rolls.