Why SP Escaped “Goonda Raj” but RJD Cannot Shake “Jungle Raj”

Both parties draw on the MY social base, but SP has successfully expanded its appeal

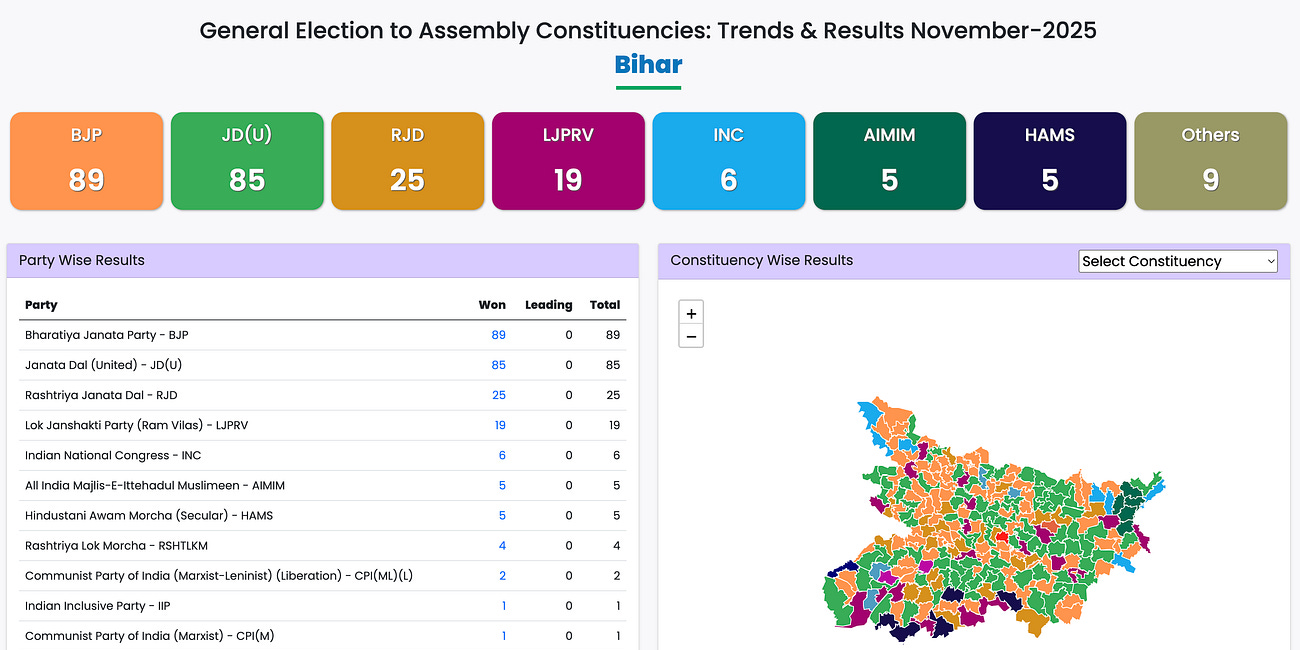

By all accounts, it appears that the RJD suffered from a negative perception of “jungle raj” even though it has been twenty years since Lalu last governed Bihar. Whether that has a decisive impact on the result will become clear tomorrow when the votes are counted. But it is striking that the SP, with a similar Muslim–Yadav base and which was thrown out of power in 2007 for “goonda raj,” was able to shed that image while the RJD has been unable to do so.

It may be argued, with some legitimacy, that both RJD and SP emerged as vehicles of social justice and that an upper-caste bias equates the politics of empowerment with the politics of disorder. That critique carries weight but cannot fully explain the divergence. In the SP’s case, the party has successfully recast itself as aspirational and modern. The RJD has not escaped the shadow. The phrase jungle raj is thus not about social base alone. It also reflects the extent of institutional breakdown and the way political parties structure and communicate their platforms.

Political parties across India are headed by second-third-fourth generation leaders. There is a need for each leader to reinvent the party in their own name to be able to effectively wield power internally. In some instances, reinvention is necessitated to expand the base and speak to the aspirations of the large youth electorate that has made itself heard, certainly, in the Bihar election and also in the Lok Sabha election of 2024. It is thus worth unpacking why the SP managed this transformation while the RJD has not, because it speaks to a broader challenge of party reinvention, which I have written about earlier.

First, by most accounts, the collapse of Bihar’s governance was more severe than the law and order deterioration in Uttar Pradesh. In Bihar, administrative paralysis, criminalization of local governance, and breakdown in routine service delivery appears to have left a more lasting public memory. However, the situation in Uttar Pradesh was bad enough to lead to a similar backlash. In fact, as multiple commentaries at the time note, Mayawati “led her Bahujan Samaj Party to power with a clear majority in the 403-member Uttar Pradesh assembly after promising to end goonda raj and restore law and order in the state”.

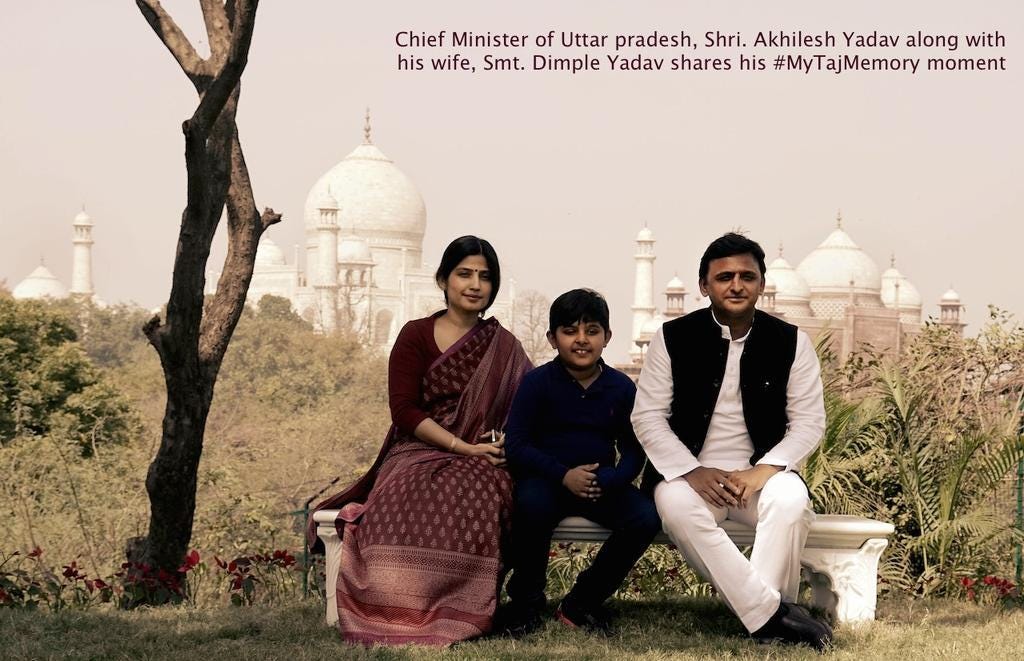

In SP, Akhilesh Yadav did not merely embody a generational shift. He presented the party in a radically different manner. His cycle yatra created an accessible, people-centric image far removed from the old strongman aesthetic of leaders leaping out of SUVs with cavalcades behind them. Akhilesh himself is personable, speaks with restraint, and smiles naturally. These cues shifted the tone of the party as much as any policy change.

Second, there was a deliberate softening of the SP through Dimple Yadav. Together, Akhilesh and Dimple cultivated the image of a modern, educated middle-class couple. This communicated stability, respectability, and a break from the party’s older machismo. Not only did Akhilesh project the image of a family man, but it was very clear that his wife had influence on him and his decision-making.

By contrast, when Lalu went to jail, Rabri Devi was thrust into the Chief Minister’s office as a proxy, not as a political equal. Tejashwi has worked hard, campaigned energetically despite physical strain, and focused creditably on jobs and youth issues. He thus remains the most popular CM face in Bihar. But he has not been able to change the moral aesthetics of the RJD: discipline, education, gender respectability, and urban polish, all of which signal order and aspiration in the wider public perception. In the absence of these cues, older narratives about disorder find traction easily.

RJD also lacks visible women leaders in its public messaging, despite Misa Bharti being strong and articulate. She could have played a role similar to Dimple Yadav in projecting generational softening and speaking to women’s aspirations, especially among younger voters. Moreover, giving a ticket to Shahabuddin’s son undercut Tejashwi’s attempt to reposition the party around jobs, governance, and youth. It signaled that the party lacks organisational structure and still depends on strongmen and that Tejashwi will not, or cannot, enforce a bottom line on the use and projection of the RJD platform. This is where the contrast with Akhilesh becomes sharpest: he demonstrated authority by purging elements within the party and asserting control.

Finally, the SP found an opening in 2012 that Tejashwi narrowly missed in 2020. The BSP had lost its sheen and faced strong anti-incumbency. Its governance had improved roads and administration but was perceived as arrogant, over-centralised, and corrupt, especially after the memorial-building spree and alleged contractor extortion. Dalit support held, but upper castes and Muslims drifted. A weak Congress and a BJP without a compelling state leadership created space for a rebranded SP. The SP used power between 2012 and 2017 to further rework its image through laptops, expressways, the Lucknow Metro, and a generally cleaner image. There was some publicity around modernising the police force and a women’s helpline was launched with much fanfare to make women feel safe. The accusation of goonda raj against the SP is still used by opponents but it no longer sticks.

Tomorrow’s count will show where the MGB stands. But the deeper question for the RJD will remain unchanged. It must rebuild not only its governance record if it comes to power but also the architecture of its political platform. Without a clearer signal of order, discipline, and aspiration, the party will remain trapped in inherited perceptions. The lesson for Tejashwi, and for dynastic parties more broadly, is that generational change matters only when it is accompanied by substantive organisational and ideological renewal.

Also Read:

Reflections on the Bihar Election and Party Campaigns

Many years ago, when I headed a national student organisation, we often debated which issues would help us broaden our appeal among students. One theme that returned in every meeting was the demand to restart student union elections in states where they had been suspended. Elections had been halted because of campus violence and other concerns, but the …

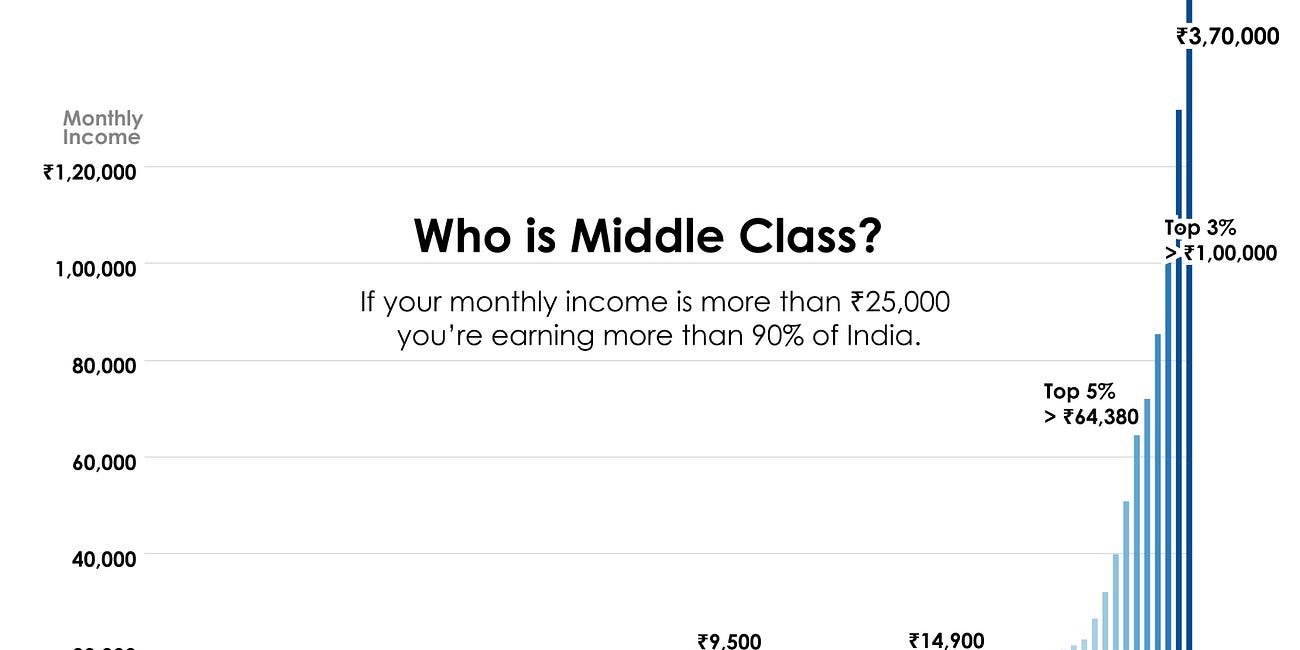

The Politics of the “Middle Class”

In India, policy elites often dismiss people’s characterisation of themselves as “middle class” by pointing to their percentile rank. And it is true. A popular chart from the World Inequality Database shows that a monthly income above Rs 25,000 (USD 280) puts an individual in the top 10 percent of earners. A government commissioned report,

Nice piece, the premise is right and the explanation makes sense. When I think about both the parties, I always wondered how I could dissociate SP from Mulayam and only think about Akhilesh and the exact opposite is true with RJD - Lalu always pops up first before Tejaswi. The optics within RJD still project Lalu as calling the shots and for him it’s not easy to shed the corrupt image among the broader electorate despite the respect he receives from his base on social justice.

Really interesting read and Dimple Yadav's role can not be overlooked. I remember this slogan from a few years back, "satta ki chabhi Dimple bhabhi" and this article made me think about it.