The Politics of the “Middle Class”

Why ignoring middle-class aspiration is liberalism’s blind spot

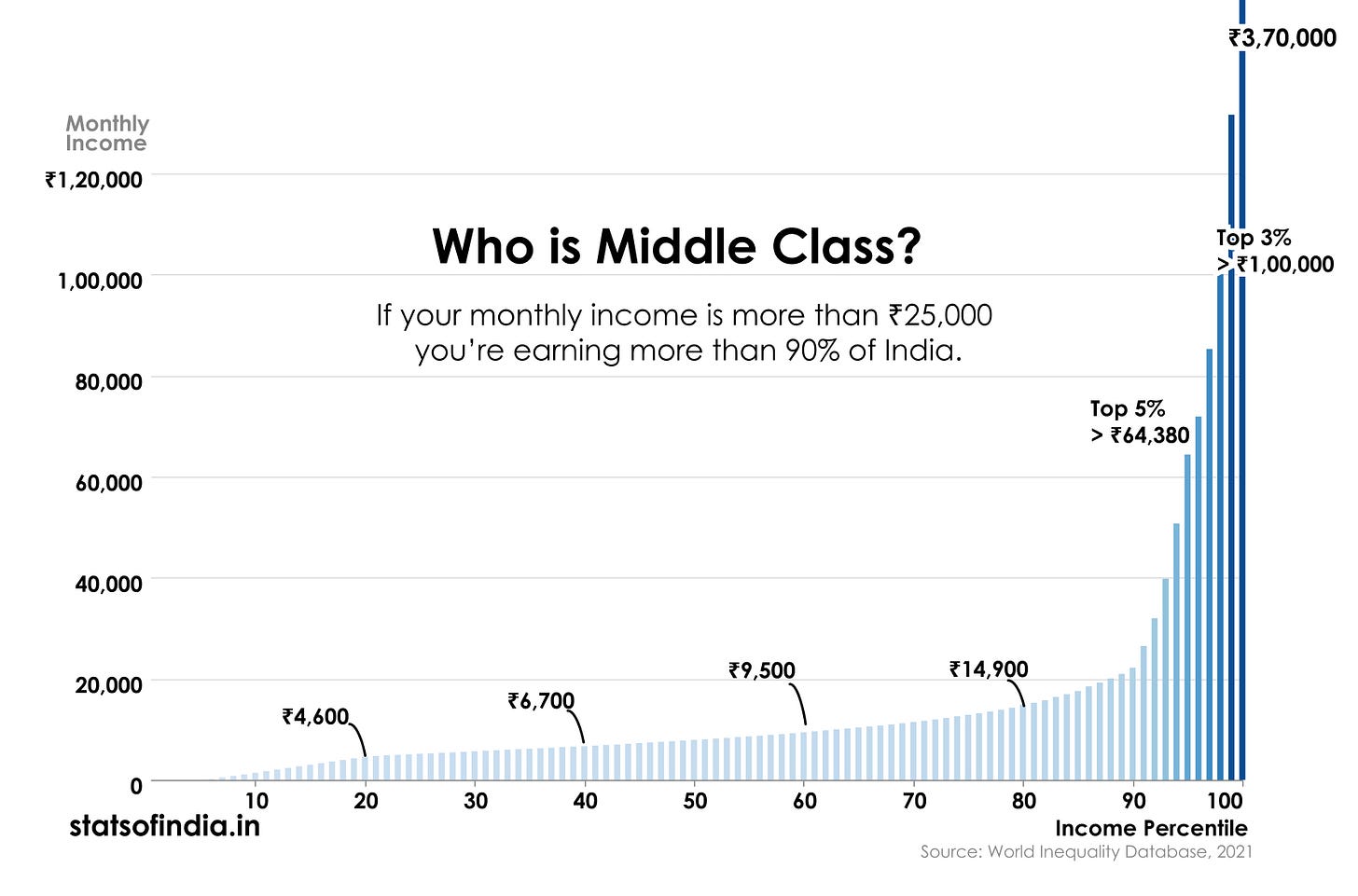

In India, policy elites often dismiss people’s characterisation of themselves as “middle class” by pointing to their percentile rank. And it is true. A popular chart from the World Inequality Database shows that a monthly income above Rs 25,000 (USD 280) puts an individual in the top 10 percent of earners. A government commissioned report, State of Inequality in India, makes the same point using PLFS data. Numbers may have increased somewhat since, but the basic point stands: a relatively low income can place someone in the top decile in India.

This is academically correct but politically tone-deaf. In politics - and certainly in India - what defines the middle class is not which percentile band it occupies, but the daily gap between aspiration and reality. The “middle class” is not a statistical category but a social one, shorthand for the striving and the status-anxious where aspiration constantly outpaces capacity. Dismissing this with data alienates rather than mobilises the “middle class”.

Brandishing percentile charts to say, “you’re in the top decile, so stop complaining,” has become a tic of the elite. But the aspirations of India’s middle class for a better life are as valid and legitimate as those of the poor. We dismiss them not because their aspirations are illegitimate, but because we have no politics for them. They are too rich for welfare. The other politics of jobs, schools, hospitals has been repeated so often with such poor delivery that it has lost credibility. So we ignore them and call them apathetic. And when they resist welfare or affirmative action, we dismiss them as entitled and bigoted.

This is not just tone-deaf politics. It is damaging our country’s cohesion. Middle classes everywhere play a stabilising role by investing in education, savings, and ambition. In India, they may be statistically elite, but they remain anxious about their children’s prospects, job security, and healthcare. They deserve empathy and respect.

Aspiration as democratic energy

In fact, democratic energy in most developing countries comes precisely from the gap between aspiration and reality - whether it is young people protesting paper leaks, farmers demanding compensation, contract workers asking for regularisation, or small businesses against GST. Middle-class aspirations for reliable infrastructure, security, stability and mobility are democracy’s most dynamic source for energy because they are not amenable to welfare transfers. The question is not whether these aspirations are legitimate, but how to channel them into a collective project of progress and equity.

The absence of a politics for the middle is one of liberalism’s blind spots everywhere right now. Welfare speaks to survival, but the middle class wants dignity, status, mobility. If politics only ever offers redistribution at the bottom or privilege at the top, they are squeezed out of the story. The Right, on the other hand, speaks directly to them - promising stability, national pride, global recognition, even cultural chauvinism. These may be hollow markers of status, but at least they register aspiration. Liberals have not even tried. A liberal politics must be able to say: we see your hard work, and we will help turn it into progress - through education, jobs, housing - as part of a collective project of nation-building.

The politics of mobility

The “middle class” in India is heterogeneous: salaried workers in the informal economy, clerks and teachers, small traders and businesses, IT professionals. What unites them is striving for progress and dignity. At present, this striving often takes the form of spiralling consumption and status anxiety. A liberal politics for the middle must instead speak the language of public goods and shared futures - quality schools, decent jobs, functioning urban infrastructure, environmental security, and a shared community. These are not private entitlements but collective guarantees. They secure progress for each through collective progress.

The problem is that the state has little credibility on this front. Decades of broken promises have produced cynicism and apathy. Rebuilding belief will require a few steps.

First, political language must acknowledge middle-class aspirations as legitimate. Mobility - the sense that life moves forward, that children will do better than parents, that effort yields progress - is a reasonable demand. Any governing politics must be able to deliver this.

Second, aspiration must be re-anchored beyond consumption alone. Given the sheer friction of daily life in India, the desire for some material comfort is legitimate. But mobility defined only by consumption can only produce endless dissatisfaction. To the extent consumption is about status, our politics must offer new avenues of recognition: civic pride, national progress, contribution to public good. It has to include collective mobility - a sense that India itself is progressing, and that each person’s struggle is part of that story. Without that, we will be left with the grasping aspiration of today that is antithetical to the collective project.

Third, politics of mobility can only resonate if people see the emergence of concrete pathways: better public universities, credible job pipelines, functioning urban infrastructure, ways to engage and participate in civic life. Otherwise, “progress” will remain a hollow promise.

The role of elites

In the short term, given weak state credibility, elites must play a role. Unfortunately, India’s elite increasingly valorise private hustle - unicorns, 80-hour work weeks, personal wealth - rather than public contribution and nation-building. This feeds the idea that progress is personal, not national, and comes with no collective responsibility.

Earlier, elites derived legitimacy by serving as custodians of national progress. Today, they derive it from global benchmarking and private wealth. To restore belief in collective mobility, elite prestige must be re-anchored in public contribution. Elites are deeply status-driven. We must thus shift the social reward structure towards institution-building and civic contribution.

This is not just about moral exhortation. If elites are visibly seen contributing to public goods, it restores credibility for politics itself. The middle class currently views both politicians and elites as extractive. Recasting elites as partners in progress creates a shared horizon of mobility.

At the same, while the role of the elite in setting norms is crucial - the risk is elite capture. National progress cannot depend on whether the wealthy choose to be benevolent. In democracies, it has to be institutions and politics that discipline elites into contributing to public good. If this seems like a tautology, it is. There is just no getting away from the fact that in democracies, politics is the fountainhead of values and norms. And politics must communicate a love for one’s country and a desire to contribute to the collective good. This is not NGO speak. It is the basic task of political parties: to put national progress front and centre.

Agenda for Liberalism

The absence of a politics for the middle is one of liberalism’s gravest blind spots today. Their aspirations must be acknowledged and channelled toward collective progress. With urbanisation advancing and poverty, however unevenly, receding, failure to do so is both electorally short-sighted and dangerous. Middle-class aspirations can be harnessed for collective nation-building or weaponised for exclusion and securitisation. Recognising these aspirations and shaping them for collective good is integral to renewing the democratic contract.

Also Read:

Liberalism Must Deliver - and Communicate - Good Governance

This essay is the third in a four-part series on rearticulating liberalism for today’s world. Liberalism once thrived as a creed of emancipation, breaking shackles imposed by communities and states. The first essay argued that liberalism failed to evolve as contexts shifted, and its own principles helped sow the seeds of its decline

Reclaiming the Nation for Liberalism

This essay is the second in a four-part series on rearticulating liberalism for today’s world. Liberalism once thrived as a creed of emancipation, breaking shackles imposed by communities and states. The first essay argued that liberalism failed to evolve as contexts shifted, and its own principles helped sow the seeds of its decline

Rearticulating Liberalism - I: How Liberalism Lost the Majority

This essay opens a four-part series on rearticulating liberalism for today’s world. Liberalism once thrived as a creed of emancipation, breaking shackles imposed by communities and states. But as contexts have shifted, its own principles have sown seeds of its decline. To regain its power to inspire majorities, liberalism must evolve. In the coming essa…

Wasn’t it eleven years ago, after an anti-corruption movement, that a person rose to power promising good days and articulating all the demands stated here? The middle class voted for those promises and continues to see that person, who can’t be named, as the messiah of this cause. It’s not clear if it is the fault of liberalism that the middle class found someone else and an ethno religious patriarch who spoke for them and brought them together. Actual numbers will show whether their patriarch has delivered on his promises for the middle class.

We can look at numbers since 2014 -

The talk vs spending or investment on education, health universities, the other basics you have mentioned for example. Them compare it with what was expected.

What if the angle to look at this is to use caste - dominant, oppressor caste, and wannabe oppressor caste groups - instead of middle class.